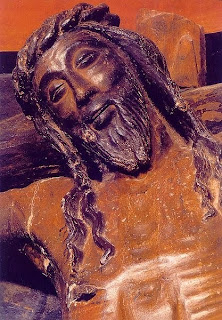

THE SMILING CRUCIFIX

The enigma of the smiling crucifix

Gerard W. Hughes

Why, to so many people, does Good Friday appeal than Easter? The author of God of Surprises thinks we prefer sin and death to Resurrection. For the truth of redemption, he turns to an unusual carved cross

I have twice visited the Castle of Xavier in Navarre in Spain. Of the many memories of that place, one keeps recurring – the larger-than-life thirteenth-century crucifix, carved in walnut, of the smiling Christ.

When any event keeps recurring in memory, it means that the event has, in some way, touched on something important to us and is affecting us now, although we may not be conscious of its meaning.

That smile raises profound questions. Is there not a danger that such a portrayal can trivialise the cosmic importance of Christ’s death, the severity of his suffering, physical and mental, the inhumanity and barbarity of his death? Even more serious: does this smile not trivialise the seriousness of our sins, the cause of his death? Could this smile be heretical, undermining the fundamentals of our faith? How must God the Father have felt, having willed the Son to die in punishment for all the sins of the world, on seeing him take it all with a smile?

Mel Gibson’s film, The Passion of the Christ, was a phenomenal box office success, acclaimed by most reviewers as a masterpiece, hailed by many Christian leaders as a wonderful means of Christian evangelization. There was no hint of a smiling Christ in that film, which focused on the Passion itself, with very little of the life of Christ before his Passion, and even less after it. Richard Eyre, reviewing the film for The Guardian (10 April 2004), begins with “What was going on at the end” said the Australian girl. “It was Easter,” said her companion. “Oh yeah, see what you mean,” said the young Australian, not seeing, as we shuffled out of the cinema?

It was a powerful film of prolonged and unrelenting torture. Yes, Jesus was tortured, reviled, subjected to the most agonising form of death that Roman genius could devise. His suffering must not be belittled, but the physical and mental agony of Christ and the brutality of his murderers is not the essence of the story; to present it as such is to distort the Good News, presenting a redemption through horror and violence.

But is not the whole message of the film to present vividly the horror of sin and the goodness of God in saving us from it, “He died for our sins”? Yes, I believe he gave his life for us, but why, and what does it say to us today? There are many different answers to these questions. Let me give one set of answers commonly given, the kind of answer which endorses Mel Gibson’s film, but an answer which can bring death, not life, to thousands.

Why did Jesus die? He died for our sins. He died because it was his Father’s will. In his agony in the garden, the night before he suffered, he prayed: “Not my will but thine be done.” As a result of his obedience to God’s will, our sins are forgiven through his sufferings. There is no salvation for the human race except in the blood of Jesus Christ. We thank him, our God and Savior, and want to spread the Good News to all peoples, setting them free in Jesus’ name from all manner of tyranny, and so work to establish the Kingdom of God on earth as it is in Heaven. With God’s help, we rid the earth of evil people and from evil regimes. People with such religious convictions in America and Britain, for example, can wage war on Afghanistan and Iraq and, in due course, can continue the good work in God’s name and for the good of all humankind in other rogue states, too.

Why are these interpretations and over-simplifications of the Good News so damaging to us and to Christian faith? It is because they focus our attention on sin and suffering, not on God, except in so far as Jesus is presented as the only escape route from our human destruction. We are saved only in Jesus’ name. In this type of Christianity, and it can infect any Christian denomination, or individual Christian, death is more emphasized than life, sin is more central than goodness, the devil more significant than God, fear is more powerful than joy, and a smiling crucifix is likely to be considered an outrageous blasphemy.

Why is it that in many churches, Ash Wednesday and Good Friday draw larger congregations than any other feast in the Christian calendar, including Easter Sunday? Are we somehow more at home with sin and death than with life and the Resurrection? Why is the disease of lingering guilt such a common phenomenon among God’s people, whose vision is restricted within their own and other people’s sinfulness, real or imagined?

How is it that we can come to assume that our will and God’s will must always and inevitably be in opposition, that there are conscientious Christians who feel vaguely uneasy whenever they find themselves enjoying anything, concluding that this enjoyment cannot be God’s will? Why is it that when we hear Jesus say “Repent”, we assume that we must do something painful or unpleasant in order to please him? Why can so many feel bad about feeling good?

We must repent continuously, but repentance does not mean doing something difficult to please God, as though God is best pleased by our masochism. Jesus, image of the unseen God, is a man of passion. “I have come to bring fire to the earth, and how I wish it were blazing already. There is a baptism I must still receive, and how great is my distress till it is over!” (Luke 12:49-50). It was love of “Abba” and of the Temple that led him to drive the dealers out, complaining that they were turning his Father’s house into a den of thieves. His actions, teaching and parables are charged with this love of his Father for all people, not only for pagans as well as Jews, but for the wicked as well as the virtuous. His passion is not just that we should all be forgiven, but that we should become one undivided person with him, our being possessed by his Spirit of freedom, of love, tenderness and compassion for all peoples and for all creation.

Jesus did not die that a small percentage of humanity should have their sins forgiven while the majority should perish. It was because he manifested God’s Spirit of love and compassion for all peoples that he was killed. Such a God as he revealed could cause havoc, undermining the authorities, both religious and secular. “The Sabbath”, Jesus taught, “is made for human beings, not human beings for the Sabbath”, so reinterpreting one of the basic commandments of God, “Remember to keep holy the Sabbath day”. And what was to become of national security if people were to follow Jesus’ programme, “love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who persecute you”, claiming that this was not just a commandment of God, but described the very being of God, for “He himself is kind to the ungrateful and the wicked? (Luke 6:35)” “Be compassionate as your heavenly Father is compassionate”: it was this love, expressed in these acts, and this teaching that led him to his Passion and death, not a love of suffering.

His love for God and for all people was stronger than fear for his own security. He did not die to suffer. He died to set us free. In St Paul’s words, “God made the sinless one into sin, so that in him we might become the goodness of God” (2 Cor. 5:21).

Thank God for the sculptor of the smiling Christ! He expresses a spirituality with ancient roots, a spirituality which emphasizes the extraordinary goodness, gentleness and attractiveness of God. In God’s light, we see light and in God’s Spirit we can glimpse the peace and love, the generosity and forgiveness which we are to become and, with God, to offer to all peoples.

from: The Tablet

.jpg)